“Media myths increasingly surround us in today’s ever more mediated world, few of which have proved more persistent than the well-worn canard about newspapers dying.”That’s the way I start the concluding chapter of my forthcoming book Greatly Exaggerated: The Myth of the Death of Newspapers, which is planned for publication next month by Vancouver’s New Star Books. The book is based on financial research I did for an article in the upcoming issue of the Newspaper Research Journal. It shows that none of the eleven publicly-traded newspaper companies in the U.S. or the five in Canada has shown an annual loss on an operating basis going back to 2006.

In fact, most are making double-digit profit margins, or more than twice the historical average of 4.7 percent for a Fortune 500 company. That’s a far cry from the 20-30 percent profit margins newspapers they routinely made before the double whammy of the Great Recession and the Internet reduced their revenues by more than half in the U.S. The decline in revenues in Canada, where the recession was not felt as badly due to more sensible banking regulations, has been about a quarter.

Just as we entered production this week, a deal went down between Postmedia Network and Quebecor Inc., two of Canada’s biggest media companies. It would give Postmedia the Sun Media chain of mostly tabloids, and with it newspaper monopolies in Calgary, Edmonton, and Ottawa, as well two dailies in Winnipeg and in the ultra-competitive Toronto market. I am still crunching the numbers on what this would mean for daily newspaper ownership concentration, but it would have to put Postmedia above 30 percent. Canada has had about the highest level of media ownership concentration in the free world, and this tightens it even further.

The most immediate effect would be to give Postmedia joint operations in four cities – Calgary, Edmonton, Toronto, and Ottawa – including monopolies in three of them. It could combine production, advertising, and circulation operations as it did in Vancouver 57 years ago, while hopefully keeping separate newsrooms. This will be subject to approval by the Competition Bureau, which will examine the extent to which Postmedia will dominate the market for print advertising in Calgary, Edmonton, and Ottawa.

The reaction has been predictably outraged among free press advocates. Some, however, have urged that Postmedia be allowed to swallow Sun Media because it is somehow challenged financially. Foremost in this effort has been Ivor Shapiro, chair of the school of journalism at Ryerson University in Toronto.

“What we’re talking about here is one threatened company . . . buying properties whose future was in doubt,” Shapiro told the Canadian Press when the deal went down last Monday. “That is way better at the end of the day than seeing both of those news organizations close down.” Shapiro repeated his position for the Saturday edition of the Toronto Star.

What we’re talking about here is two organizations that were on a death watch. I’d rather have one news organization that is not on death’s door, than two news organizations that are. Together they are stronger competitors than they were apart.No, together they are not competitors. Together they will be able to gouge advertisers and short-change readers in Calgary, Edmonton, and Ottawa, just like they have done in Vancouver for the past 57 years. These two organizations have hardly been “on death’s door,” as Shapiro puts it. They have been earning enviable profit margins. They just want to make more.

Here is a truncated version of my compilation of the financial results since 2010 for all five publicly-traded Canadian newspaper companies, which own about three quarters of newspapers north of the border.

How could the head of one of Canada’s largest journalism schools be so mistaken about the state of health of the country’s newspaper industry? Well, let’s just say that Professor Shapiro isn’t the only one laboring under the illusion that newspapers are on their last legs. That is the whole thrust of my book, and it’s a complicated tale. Ben Bagdikian called it “the myth of newspaper poverty,” and it has been used to advantage for decades by publishers looking to get around anti-trust laws that were designed to prevent anti-competitive behavior. Newspapers, after all, have considerable power over public perceptions, and they have used it to advantage for decades.

One of my favorite studies cited in my book examined how large U.S. dailies covered the short spate of newspaper closures during the Great Recession. It found their coverage contained “over-amped drama” and even “tabloidization,” with more than a quarter of all stories containing death imagery. “Newspaper journalists often fail to contextualize their reports with a comprehensive understanding of the economics of their industry,” noted the study. “They rely too heavily on the views of newspaper publishers and too little on empirical data.”

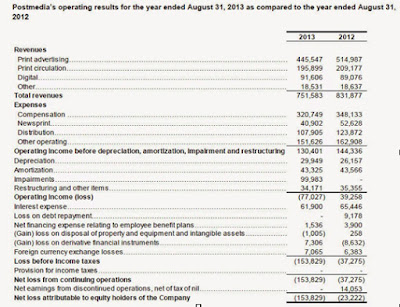

Toronto Star columnist Rosie DiManno also buys into the misconception that Postmedia is “bleeding money, staggering under accumulated debt and struggling to make its payments.” Even the usually-incisive Donald Gutstein bought into the myth that Postmedia is “hemorrhaging money” in his recent dissection of its ownership by U.S. hedge funds. Gutstein reported that the company lost $154 million in 2013, but that included extraordinary charges against income of $100 million for asset impairment, plus $34 million for restructuring costs, which means they laid off a whole bunch of people and had to pay them severance. Asset impairment is a classic “paper loss” that simply means the estimated value of the business went down. That has to come off the balance sheet of assets and liabilities somehow, and it does so in the annual profit and loss statement. Here is Postmedia’s for 2012 and 2013.

Note that interest expense eats up about half of Postmedia’s operating income, but that amount has been going down as the company pays off its debt with its positive cash flow. What I find most interesting, and which I wasn’t able to get into in my book, is that as a result of these financial gyrations it appears Postmedia paid no income tax in either 2012 or 2013. Suggestions for further research?